Anna Cigarini, 17 June 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic has stressed the role that citizen science may play to react and respond to disruptive societal challenges by highlighting the importance of scientific evidence to inform decisions in times of uncertainty. The COVID-19 lockdown has also forcefully increased the use of ICTs, facilitating the sharing of knowledge and data, boosting self-organization, and solidarity and mutual support, while also fuelling controversies around privacy and security.

If on the one hand digital technologies may serve as a catalyzer of human and civil rights violations, the increased availability and use of ICTs could also be seen as a way to expand opportunities for citizen science beyond crowdsourced participation. Indeed, digital platforms already provide a number of diverse forms of interactions between professional researchers and citizen scientists, from spaces to build, engage, sustain a community and connect with other citizen scientists to repositories of tools, guidelines and projects (https://eu-citizen.science/).

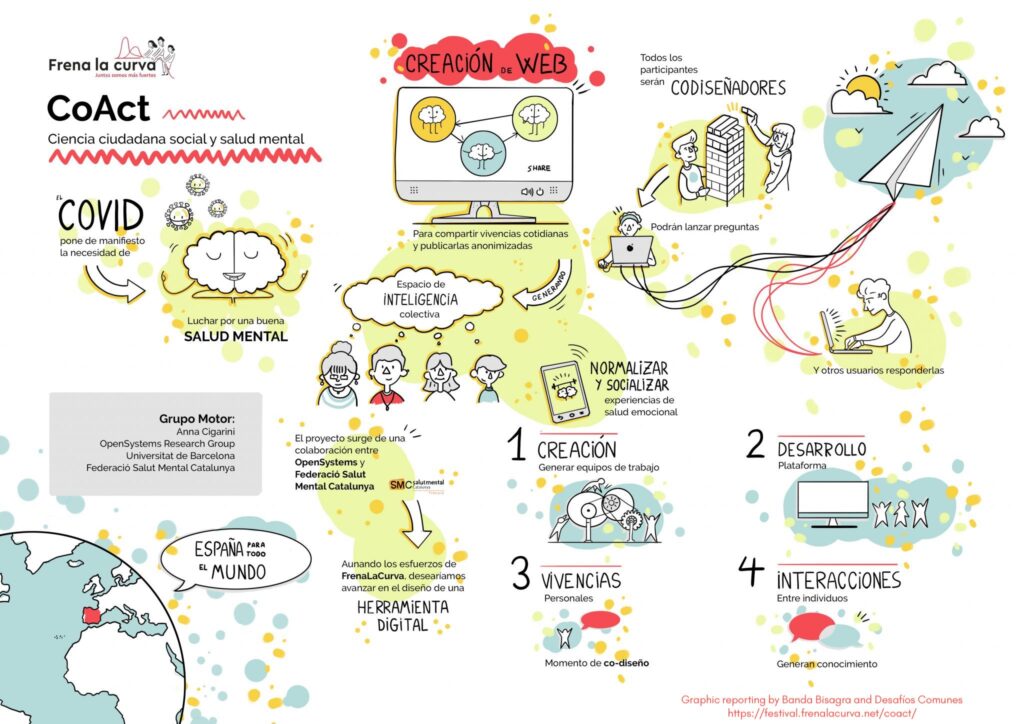

In an attempt to respond to the COVID-19 crisis and to explore how the decisional role of citizen scientists could be elevated beyond data collection through digital tools, we promoted the CoActFrenaLaCurva project during a one-week digital hackathon (https://festival.frenalacurva.net/) organized by the network of citizen social laboratories and maker spaces of Spain, Central and South America. The project, which is based on the CoAct R&I Action on Mental Health Care, aimed at co-creating a citizen social science platform to collect personal stories and strategies of care to map the network of informal social support for mental health during and after the pandemic (http://coactfrenalacurva.net/).

The methodological approach followed citizen social science principles by giving project members an equal seat at the table through active participation since the very beginning of the co-creation process. Telegram was used for daily communications, coordination and feedback. Google docs were used for collaborative editing and production and stored in Google folders, while Jitsi video conferences -recorded upon oral consent- were used as spaces for discussion, decision-making and validation throughout the different phases of the co-creation process. The project combined a wide range of expertise from different geographical origins, from individuals with an experience of mental health and health professionals to web designers and visual artists to representatives of administrations and activists from Europe, Central and South America.

To get started, two welcoming video conferences were organized to accommodate participants from different time zones in order to map expectations and expertise. Via two other video conferences, three thematic groups were formed on day 2, each one with different scope: a) the group in charge of the development of the platform content and visualizations, b) the group in charge of the communication strategy, and c) the group in charge of the platform design and its development. The participants self-selected themselves into one or more groups. Each group had between 4 and 13 participants that were comprised by one coordinator, a core group of participants and a dispersed group of in-and-off contributors. The following two days were devoted to prototyping the digital platform in separate groups by means of a dedicated Telegram chat for coordination, a shared Google doc and Drive for collaborative production and storage, and a daily video conference for decision making and validation. On day 5, two general video conferences were organized to assemble and discuss the work of each group to put the pieces together. On day 6, we had a final video conference intended as a space to validate the resulting platform (http://coactfrenalacurva.net/), which was publicly presented the day after during the open innovation festival FrenaLaCurva (https://festival.frenalacurva.net/).

The project planning and video conferences were facilitated by the social architect Itziar González. The author (Anna Cigarini), Isabelle Bonhoure and Josep Perelló from Opensystems – with the support of Bàrbara Mitats and Machús San Pio from the Catalan Federation of Mental Health- coordinated the project through the common Telegram group while also being in charge of the coordination of one thematic group each one of them. The participants worked together acting as domain experts of their own needs and experience. Principles of transparency, openness and horizontality were deemed critically important since the very beginning to create a supportive atmosphere from the start and to provide a welcoming forum for all participants throughout the process. The digital tools were used to share participants enthusiasm, ideas, knowledge about first hand experience of mental health and support strategies, alternative communication practices and user experience design.

Feedback from participants showed that the digital tools helped to create a space for collective learning about communal values e.g. collaboration and solidarity – a recurrent theme across participant assessment of the impact of the process. Digital platforms and tools also enabled different levels of participation to co-exist at the same time, namely project coordination, a core group of co-researchers and a more dispersed group of in-and-off contributors. This was made possible by continuous feedback and transparency about the project development, which facilitated horizontality and also helped to overcome personal and contextual barriers that hinder sustained engagement in collaborative projects. Furthermore, digital platforms centralized the set of common resources, stories and tools co-produced during the project and were openly accessible to participants beyond the project end.

The broad variety of expertise and geographical origins, which would hardly be possible in physical settings, helped to amplify the scalability and reach of the initiative while creating a community of committed ambassadors for the future project development. Contrary to physical settings, however, digital tools posed extra challenges of coordination among geographically dispersed and heterogeneous forms of participation. Digitally mediated communications are also more impersonal and detached than face-to-face communications, and experiencing empathy online happened to be at times more challenging. Co-creation processes that shift to online landscapes further require the design of tools for informed consent procedures and information access and sharing, that is to be adapted to distributed knowledge settings. Finally, concerns are raised about equitable digital access and literacy, a particularly significant issue for already marginalized collectives.

Overall, reflections on the project suggest that digital infrastructures and tools may well serve as an opportunity for citizen science to move towards more sustained forms of engagement in the research process and to create a citizen social science community of practice. The increased availability and use of ICTs, however, also calls into question who may participate or not in the process and how. If digital technologies are to be rolled out in co-creation settings and thus help to elevate participation in citizen science projects beyond data collection, it is important to explore and define inclusive and rights-based digital practices that provide new options of democratization of knowledge creation and ownership, favoring access and derivative work.