Crowd-sourced techniques have the capacity to collect complex and rich citizen-generated data. However, the interpretation of this data can be different and diverse depending on who is reading the data. Professional scientists can indeed have a biased perspective, may miss important aspects and thus cannot respond to the interests and concerns of the Co-Researchers. Opening the data interpretation process not only increases inclusion and diversity of perspectives in narratives from the research results, but also allows to obtain socially robust and actionable knowledge. The collective interpretation is important to increase the sense of ownership of all participants and to continue the ongoing discussions related to the social concern with concerned participants.

The method can involve between 5 and 20 persons per session. It is recommended that the groups involved share a common concern in the discussions. It is also advisable that the group has been part of previous steps of the research so that they are better aware of the context and the motivation of the CSS research. Otherwise, it would be necessary to dedicate an important effort to provide the group with a complete picture of the research. In our case, Co-Researchers involved were citizens with mental health problems and family members, and caregivers of persons with mental health problems. We ran a shorter and less interactive set of sessions with the Knowledge Coalition, which comprised persons from local organizations (civil society organizations, academic institutions or research organizations and public administration from different levels) in the field of mental health.

Which material is needed depends on the topic of the project, the data set, and the profiles of the Co-Researchers. In general, it should invite interaction, actually give insights, and ask for contributions from the Co-Researchers. The material should provide some intuitive components, so that everyone can join the discussion, but still be scientifically rigorous and actually interesting. We got inspired by a local game association called Revolúdica. They showed us how to adapt the basic principles of short duration interaction games to different contexts to achieve different discussions and reactions.

- Professional scientists explore data taking the widest number of possibilities. Exploration must include analysis on who is providing citizen-generated data, the dynamics of their involvement, the impact of external inputs such as dissemination activities, and most importantly the data collected that responds to the social concern. Ideally, different professional scientists should be involved in this task to increase the diversity of techniques in the analysis. Each one should take a different route to explore the data. Periodic meetings should then serve to share the different explorations and plan next steps, e.g. on a weekly basis. The several data scientists must adopt an as much as possible neutral position and avoid raising any interpretation or explanation about the results. Qualitative analysis is also encouraged.

- A first workshop (3h or more) is organized to discover basic data on who and on how many persons have contributed in a crowd-sourced manner in CSS research. Professional scientists organize a workshop for the Co-Researchers. This session is important to frame the research and to make sure we interpret data collected being aware of what are the different components and backgrounds of the data collected. It helps to structure the workshop into several interventions of 10-20 minutes. For instance in our project that used a digital tool, the Co-Researchers first were asked to sort the different components of the digital tool, mostly to jointly remind how everything worked. Then, we discovered together which profiles of participants used the digital tool, asking the following two questions: Whom would you like to have used the digital tools? Who do you think actually used the tool? Then we gave the results of what was actually observed in the tool, and how this is representative of the entire society. This four-step procedure was repeated for different profiles, e.g. gender identity, age brackets, and the like (see Gallery). The method was inspired by a recommendation of the Open Knowledge Foundation and its initiative “School of Data”. The underlying principle is to first ask the expectations, so that the actual result can be related to and it can be understood better. After that, four more interventions discussed basic statistics on the outcomes of the digital tool. All interventions were planned in a playful way, to lower the fear of not understanding something and to get Co-Researchers engaged and discussing.

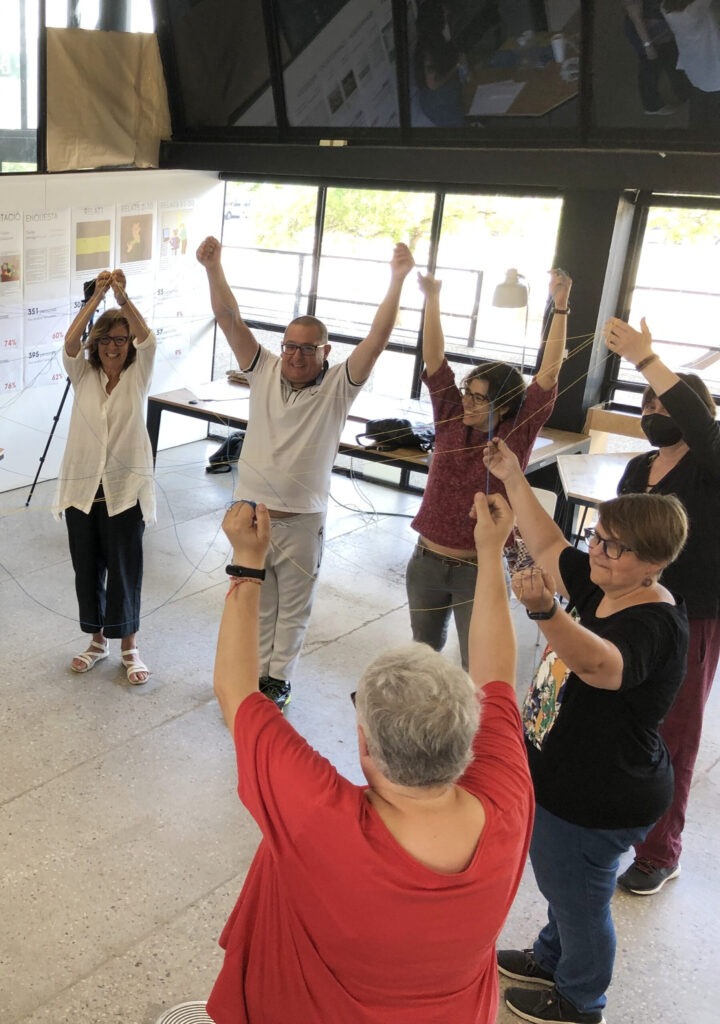

- A second workshop (3h or more) is dedicated to explore results of a deeper analysis of the data. The level of this analysis could already be comparable to what later will be published in a scientific paper. Again, the focus lies on touchable material, and to translating scientific concepts into intuitive gamified interventions. This is a key workshop to identify the most relevant results. The discussion can help to better interpret outliers and minoritarian positions. The session thus provides meaning to each result and juxtaposes different interpretations to the same result. It is indeed possible to look at particular results but also present more sophisticated analysis in a playful manner. In our case, the analysis method builds on Network Theory, so we actually invited the Co-Researchers to reproduce such a network with strings and give their interpretations and thoughts.

- A third workshop (3h or more) is mostly oriented on delivering actionable knowledge and to link it with policy recommendations. Here, we combined the results from the data with the Co-Researchers’ thoughts and interpretations, collected in the former two sessions. In our case, we formulated twenty-two observations: short phrases in easy language that represent a fact we can support with data and which the Co-Researchers can use to support their calls for action to policy makers.

In order to give the Co-Researchers (who voluntarily contribute their limited time) a maximal impact, we recorded the voices and transcripted the interventions to collect all interpretations and thoughts. Comments and discussions in a session allowed professional scientists to make additional analysis between sessions. This additional data analysis was presented in the next session.

Also, a data report was sent to Co-Researchers right after each session. They thus had more time to further reflect on the data and they could share additional reflections in the next session.

It is highly recommended to not only use a screen, but to materialize the data on printed paper or other touchable items to make the data liveable and tangible. This will help to distinguish different aspects of the analysis visually. In the best of cases, the material is designed in a pedagogical way that helps the intuition of participants to understand the presented data. To combine slides with data on a screen with printed posters on the walls allows to create a kind of gallery in which the participants can move and ask questions and comment.

The space for the workshops would ideally need big walls and large tables. The walls can display the different data panels, plenty of different observations or facts. In our project, each workshop was divided in two with a coffee break in between to favor informal discussions among Co-Researchers.

It is possible to include a co-evaluation before and after the whole set of sessions. Before starting the sessions, it can help to better identify common goals and expectations of each participant. After the sessions, it can help to better reflect on the whole process and to gather feedback for future projects.

SDG goals and data sets related with or without citizen science practices can be addressed in these sessions to allow Co-Reseachers to better connect their daily and individual experiences with more global data sets.